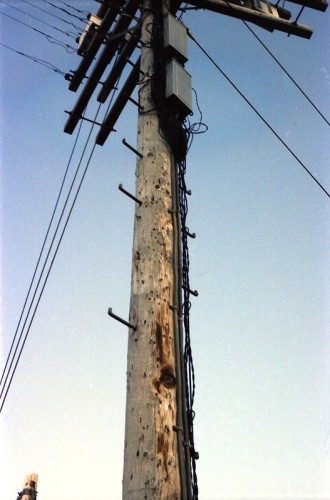

The site today, west edge of Tyndall, South Dakota, 50A highway

Nominating the First Open Wire Toll Lead to the National Register: A Drama in Five Acts

By Douglas G. Schema

Entracte: Overture . . . Lights! Intro . . . please!

The story I’m about to impart is based on my true, personal experiences with the Bell System (AT&T), Northwestern Bell Telephone Company, national and local politicians, important personalities, professional organizations and museum professionals. In retrospect, this story has lost none of its vivid power, emotion to persuade, nor have recollections of its positive images faded. There have been no “what ifs.”

This narrative has never been shared publicly before. And this . . . feat . . . had never been previously attempted. To my knowledge, whether at either the local, state or national level, during the preceding decades, there had been nothing to compare, nor to measure. To reminisce about this episode, from a viewpoint of over thirty years, amazes in regards to the time that has since now passed, and the fact that I was in my late 20s when this preservation campaign began. Today, the event stirs great emotion within, even when driving through that area many years later.

No public credit for this accomplishment was ever forthcoming. There were no acolades. AT&T, U S. WEST, the Telephone Pioneers, (Quest . . . or whatever it calls itself today) have never benevolently recognized three years of philanthropic efforts on my part to improve public perceptions of Northwestern Bell, or its impact on regional and local history. There is no historical plaque. . . and that probably will never happen.

But . . . what do I care? Something else was far more important to me than an ego-driven project: it keeping an artifact alive. Preservation of an outstanding artifact; a way of life; a craft; a unique but eminently conventional piece of landscape furniture, taken for granted–until only one or two remained. That was my satisfaction. And, I feel all the more satisfied for for them.

However, the bona fide purpose of my consistent efforts on this open wire lead’s behalf were tangible and singularly important: my great satisfaction in preserving an element of a rapidly disappearing piece of Americana as well as technical history and positively drawing positive public attention to it. Before this neoteric, somewhat funky, and unorthodox effort emerged, no one to my research efforts had ever embarked on nominating an in situ variant of open wire toll facilities to the National Trust for Historical Preservation.

Once committed to this quirky, but meritorious, little single-man project, I had hoped to model this project on what had been learned before. Perhaps . . . someone or some group . . . had done this . . . before? Might we join forces, learn from their mistakes, build on their experiences to publicly expose this line for the importance that it represented?

What my in depth research found was . . . a complete vacuum of past know-how. No one in the historical field had ever considered this particular “artifact” as representative of Americana. This news hit me like a brick–or a 300 pair loading coil! What? No one has ever tried this previously . . . seriously, now, these lines must mean something to the communications companies, surely . . .?

Instead, research found a few good and some great AT&T and Independent Telephone Museums in corporate centers, such as Southwestern Bell’s in downtown Dallas, at their Akard Street headquarters, or at a county museum: the Museum of Independent Telephony in Abilene, Kansas and a few out west in California at Pacific Bell in San Francisco, California. That’s well and good. Unfortunately, many of these historical collections were greatly removed from public inspection except through private invitation or tour groups.

Now . . . don’t get me wrong. Their efforts–and those of private collectors are greatly meritorious. Preservation of telecommunications items are a real find–especially in light of AT&T’s and other major independent’s own efforts to “line wreck” their own heritage. Suffice it to say that accounting has played a major role in insuring most historical central office, switching, toll lead and repeater equipment never sees the historical light of day. I know of episodes at the Lincoln Telephone & Telegraph-AT&T demarcation station (hut) where old equipment for carrier, reed filters, other hardware was sledge hammered to destruction, so it would satisfy the accounting people at headquarters. Carrier and other electronics were condemned to death by accountants so that such equipment could be removed fromt the books and thus . . . no tax paid on existing hardware.

Unfortunately, that was also a generously revealing means to exonerate the corporate accountants at the expense of technical and corporate history. So, locating much historical telecommunications equipment, whether in the C. O. (Central Office), or in a hut, vault, handhole, or up on a pole, could be both a harrowing and frustrating experience for those of us with a passion for technical history. I can’t tell you how many times attempts were made to procure equipment from famous facilities and the answer was typically the destructive denouement of these artifacts. And, while the communications companies put “communications” in their names, the significant lack of actual “communications” thorugh the various corporate levels was as vacuous as was the empty experience I possessed at attempting to preserve an open wire line.

Add to this, the monumental political and epic technical transformations occuring at the time of this little exercise in South Dakota. The all mighty Bell System had lost a number of legal battles and was ruled a “monopoly” on various levels. This “Battle of Giants” pitted the Federal Government against the world’s largest corporation: AT&T.

While I won’t go into fine detail about this particular event, it can be said that the government sought a divestment of AT&T assets. The FCC Chairman at the time called the settlement “a brilliant masterstroke on the company’s part.” The major winners were considered to be the stock owners of AT&T. Unencumbered with the local regional Bell operating companies (RBOCs), it was expected a more prosperous AT&T would skyrocket.

The arrangement was pretty simple: stockholders maintained an original number of shares in AT&T and received one share for each of the “Baby

Bells.” These seven new regional companies, for example in our area (Northwestern Bell Telephone Company in the five state upper Midwest), received one share in for every ten shares AT&T administered.

Now, it was very clear to most–and this was the greatest expectation of Wall Street and Main Street–that this “breakup” would allow customers a lower long distance calling bill. Local service was another issue: easily, many anticipated local prices would go up. One has to understand a very important fact about this situation: long distance prices subsidized local calling prices. The consequences of this decision by Judge Harold Green had substantial and immediate consequences for formerly Bell System customers.

On January 16, 1981, U. S. Court Judge Harold Green allowed both sides of this contentious issue to negotiate an out-of-court settlement. In the interum, Ronald Reagan had deposed Jimmy Carter in the presidency and the White House had changed both hands and philosophies. Reagan’s Justice Department had been pressured to reject any settlement based upon “spinning off” AT&T’s regional operating companies while retaining its manufacturing unit, Western Electric, its research component, Bell Labs, and its long distance transmission division, Long Lines. Bickering behind closed doors continued but in the final analysis, the U. S. Anti-trust Division finally reached a momentous verdict one year later: in late January 1982, AT&T was directed to divest itself of two thirds of its total assets.

In doing so, the regional local company, Northwestern Bell became U S WEST, whilst other “Baby Bells” and their numerous employees endured similar organizational evolutions with their particular Bell regional units to conduct business in their exclusive operating territories. It was all very confusing to the customers . . . it was all very confusing to the employees. Depending upon the employees’ choice of employ, it clould either be a path directly to potential job layoffs (previously unheard of in the “job-for-life Bell System culture”) and possible preemptive retirement or continuation of the prosperous status quo. While many AT&T personnel with whom I had personal aquaintance and familiarity, chose to answer the question: Who do you want to work for? AT&T or the Baby Bell operating companies?

Many assumed that (still) mammoth AT&T–with its grand assortment of assets, resources and talent, accompanied by its managerial history and enduring large scale entrepreneurial competence–would clearly survive over the tenuous, if not certain negative potential fates of the local RBOCs. What possible future would exist for U S WEST, Ameritechs, Pacific Telesis, Southwestern Bell et al? Layoffs were predicted and virtually certain with a jump to the little new companies. A number of AT&T employees warned their local level colleagues that they’d better move to AT&T or not survive the new chanages.

A lot of decisions were made in those weeks. Pensions, payscales and working conditions were very important to these employees. Either the employee jumped ship or stayed where he or she worked. Many went directly to AT&T.

And then . . . the unexpected occurred. AT&T within a short interval, sent layoff notices to numerous employees at Omaha’s Western Electric Works, the Underwood, Iowa Regional Distribution Center, AT&T’s local offices in cities and towns around the area.

On the other side of the fence, were the holdouts in the former Northwestern Bell Telephone Company organization, now renamed U S WEST, and whose headquarters had moved from Omaha to Denver. These staffers found few layoffs with life and career assuming a new, yet generally familiar path. Former AT&T employees who had been suddenly laid off, found their immediate calling by finding employ at companies such as NEC, Fujitsu, Alcatel, Rockwell, Avaya and others.

Many Northwestern Bell employees in Omaha were transfered to the new Denver center. Omaha ceased to be the center of what had been Northwestern Bell, as Pacific Northwest Bell and Mountain States Telephone & Telegraph became part of the new organizational entity. A dramatic change had overtaken the Bell System, never to be reprieved.

This project’s record file–easily topping three inches in depth–in a spiral ring notebook, is a brief but engaging look at public policy in the guise of a preservation effort. It would be impossible to share all the correspondence, but we will try to capture the essence of this project here, and I hope you will enjoy the trip.

Our little narrative commences shortly before this thunderous corporate and judicial avalanche of national change . . .

![]()

Act One: The Awakening

Junction of Tyndall-Mitchell/Tyndall-Wagner Toll Leads, 1979.

Junction of Tyndall-Mitchell/Tyndall-Wagner Toll Leads, 1979.

From the earliest years I can recall, open wire communications plant stirred in my mind. At three years of age my parents recall my pointing vigorously at the poles as they wizzed by on U. S. 16 between my grandparents home in Geddes, South Dakota and Rapid City, our home at the time. There were no Interstate highways at that time. U. S. 16, which has been largely been decommissioned in South Dakota as finished segments of the new I-90 took its place, was a two lane road of 1940s design vintage. It stretched non-stop from the Minnesota border to the Wyoming State Line.

Two ten pin arms on stout little poles grazed the edge of the highway easement for a significant amount of its length–probably from Phillip at U. S. 83 to Rapid City. I can still recall the glistening spans of wire in the late afternoon, just about sun set, when the glare would not allow any details of the landscape except those whose surfaces could shine back in return.

U. S. 16, with the exception of a small portion in the Black Hills, has lost its official numerical moniker and I-90 is exclusively the path of the big trucks, car traffic and buses, pulsing east and west in a never-ending stream to complete their northern Great Plains journey.

The remanents of the old highway, U. S. 16–many which were not overlaid by I-90, exist today. These quaint little backroads have been downgraded to a strip of pavement linking small towns with country road or state highway status. You can find them today.

By the late 1950s, our family had moved to Southwest Iowa. There one found larger populations, more traffic and the heat and humidity one expects in Corn Country.

But, my relatives in South Dakota had not moved. My grandparents in Tyndall and Geddes, South Dakota, until their deaths in the early 1960s and 1980s, respectively, had remained. An aunt and uncle remained in a small county seat town called “Tyndall,” were still living there. My uncle had been Chief of Police in Tyndall for many years and enforced a “no nonsense attitude” there. He was remembered.

Some of my cousins farmed–quite successfully–just a few miles north of where George Armstrong Custer had encamped his 7th Cavalry men in the summer of 1874, on their way to Ft. Abraham Lincoln. A small cemetery marks the spot overlooking the Lewis & Clark Reservoir on the Missouri River. Reliable documentation has it, General Custer chose the spot on their way west from Yankton to camp because a small stream afforded plenty of drinking water. Poor water leading to dysentery struck down about a dozen of his (lucky?) soldiers. Consequently, their graves are found at a site overlooking today’s Gavin’s Point Dam reservoir. The remaining (fortunate?) solders embarked for their fateful mission to Ft. Abraham Lincoln, near present day Bismarck, North Dakota, and then on to their fate at the Little Big Horn in Montana.

My first cousin’s husband represented and sold irrigation equipment for Valley Irrigation. Their large farm could be reached from South Dakota 50 half way south between Tabor and Tyndall. Today, the farm is still in the family.

Now, you wonder, why would I burden you with a survey of this dreary “relatives” stuff? Well . . . this information will begin to form some very interesting pieces when we begin to assemble the pieces of this remarkable puzzle together.

Entering Tyndall on SD 50A

Entering Tyndall on SD 50A

This scene is looking east, just before the Bon Homme County Fairgrounds on the right and the city park just across Birch Street. This road formerly was South Dakota Highway 50 Alternate, but is considered a county road before it enters Tyndall and its successor is now called 3rd Street.

The communications line is unremarkable in the aspect that it was like many similar leads entering a town from a rural district–a sight quite common during the first half of the Twentieth Century.

Looking east on South Dakota 50A Highway towards Tyndall, 1982.

One interesting glimpse of the toll lead’s past was December of 1971 when one Friday night, my grandfather died . . . and it happened to be be on my eighteenth birthday, which has been indelibly etched in my mind.

Meanwhile back in Iowa, funeral preparations had begun. The weather was to be very blustery for that particular weekend, so this event came at a troubling time for travel. . . (of course, what death is ever convenient, although weather can be more cooperative?). Internment was to be in a Geddes, South Dakota cemetery. By the time the cortege left Iowa on the way north, freezing rain began to fall. Before long, a full scale ice storm preceded a blizzard just north of Onawa, Iowa–and morphed into a major late fall snow storm paralyzing highways and travelers.

By the time we had travelled beyond Vermillion, broken tree limbs, power lines and wayward cars spun off the highway, were commonplace. Ice was everywhere! Travel was treacherous and cautious. By the time we passed through Tyndall, I recall noticing the landmark open wire terminal pole at the edge of town–or what was left of it: a tangle of wires which looked as if a calender full of spaghetti had just been dumped in the bar ditches where aerial wire had previously hung. The original 1931 terminal structure at the edge of town was a wreck; its mangled top broken off between the six top buck arms and lower four but folded over and encrusted with ice. Some of the tangent structures were broken an laying in the ditch. Wire layered the ground. Typically in such areas, freezing ice was less of a problem than simply . . . heavy snow. It either rains or snows–little in between. This just happened to be a relatively rare event.

On the way to Wagner, most of the rural electric three phase lines were down, with broken pole tops and conductor draped in artistic fashion every which way across fields and highways.

The funeral and internment the next day–a Sunday–was in the midst of a raging blizzard. The snow was deep, the 35 mph. 25-degree cold winds, were driving the snow horizontally. After church services, the hearse drove to the cemetery and slid on the ice, imbedding itself in the ditch where he curve approached the cemetery. The palbearers had to lift and carry the coffin far further than they had ever expected. The pastor could hardly be heard as he quickly made final comments and a prayer before internment. It was one of the worst ice storms and blizzards to hit that part of the midwest in many years.

Returning to the site in better weather–and another season, late spring–I was greeted by the same graceful open wire near Tyndall, but loaded with lots of splices and a new terminal structure. This pole, a 1968 vintage 40′ pole, took the place of the old knotty gray behemouth which had greeted us every summer for twenty years before.

Ice storms are rather rare to the upper midwest; it either is too cold for rain (and ice) or too warm for snow. This was the only ice storm I had recalled in this area as it is much more common to see them on the “I-70 Corridor,” that is, the mid-south to mid-plains regions of the United States.

Thus . . . you have some background on this particular structure and why it appeared relatively new compared to its 1931 companions.

Mitchell-Tyndall Lead looking north

10 miles north of Tyndall. My heart sunk when I saw this sight!

10 miles north of Tyndall. My heart sunk when I saw this sight!

128 line wire wrapped around fence post during line wrecking, 1979.

For Leads From Whom The Bell System Tolls . . . the Autumn of 1979

In the summer of 1979, just prior to my entering graduate school that fall, a trip through south central South Dakota jarringly awakened me to the fact that nearly all the open wire I remembered in that part of the state had been removed or was nearly all gone!

Turning a corner on S. D. 46 onto a southbound country paved road to Tyndall, I was unpleasantly surprised by what I didn’t see: the familiar double buck-armed ten-pair Tyndall-Mitchell lead leaping up to jump its wires across the highway easement. There was . . . nothing but emptiness . . . where the lines once stood. My heart dropped. Oh, no . . . this couldn’t be! Traveling a few miles down the road to the south, the wires came back again on the west side of the road, but were rudely tied to a low fence post. The remainder of the line was intact! But death was clearly on the horizon. When arriving at the northwest corner of town, the familiar old junction/terminal pole was there and the line extending west to Wagner remained.

Those emotions got me to stirring. How much other aerial wire in South Dakota had been removed . . . most of it? Or was I fortunate enough to encounter the last vestage of this remarkably American landscape element?

My Northwestern Bell connections informed me: regarding Nebraska it was deceased; defunct in all of Iowa, had succumbed in Minnesota; was inanimate in North Dakota. What little remained was that little stretch near Tyndall (and one other exception which we’ll go into a little later). It just happened to be where I had some control over the situation and knowledge of the region.

Even with graduate school staring me in the face, I wanted to get something done. Seeking to obtain parts of this line at linewrecking was one possible solution, but there had to be something more enduring and publicly valuable.

What about nominating this line (just a few poles north and west from the apex of the junction/terminal structure) along S. D. Highway 50? Surely, that couldn’t be too expensive? Perhaps the Telephone Pioneers would like a little good publicity and they might even be willing to impart some of their loving care on this old 1931 line? And the State of South Dakota? They, like most states, have a historical survey group and might find something like this project of interest, of merit and support it?

Pursuing this effort on top of a busy 20 hour graduate school schedule, while employed as a Teaching Assistant, was going to be a challenge. To the degree of challenge I encountered was beyond my original expectatons.

With research libraries within my reach, and with U. S. Government and state documents available, the U. S. Department of Agriculture Soil Surveys proved to be extremely valuable. Many of these surveys are photographic detailed maps from above with detailed land survey information. South Dakota and Bon Homme County was no exception.

Detailed photos taken when a kid through the last 20 years had been already compiled of many of the unique structures on the line. There were over seven alley-arm type two ten pin structures passing a cemetery and tree obstructions. The terminal/junction structure was intact, was wired and equipped for toll operation at O-Carrier frequencies, plus some other paraphanelia of interest. The line northbound possessed a little later construction techniques, including Preformed vibration dampers, some six pin arms, side bracket construction and numerous drops, terminals and hardware. This line appeared to be a supreme candidate for nomination.

On March 27, 1980, armed with months of research materials on the geographic site, evidence of value, technical data, lists of politicians, local newspapers, county officials, possible professional organizations, and just a plethora of documentation, I took time to write a letter to the Vice President of Northwestern Bell South Dakota operatons in Sioux Falls outlining my vision for this little piece of preserved line, how it could be identified for future generations with South Dakota history, where possible support could be found to maintain it, and a little personal background. Could you help me to assist your company and technical history in one swipe?

Other letters went out: The National Telephone Pioneers of America in New York, the Editor of NWB News (Northwestern Bell), in Omaha, the Director of the South Dakota State Historical Society, the President and Secretary-Treasurer of the Antique Telephone Collectors Association, General Manager of the Telephone Artifacts Association, the South Dakota Department of Education & Cultural Affairs, the Secretary of the Society for the History of Technology, University of California-Santa Barbara, (then) U. S. Senator George S. McGovern (D-SD), U. S. Representative James Abnor, Second District Congressman, the Editor & Publisher of the Tyndall Daily Tribune, the Field Representative for the National Trust for Historial Preservation, Director of the Heritage Conservation & Recreation Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, President of AT&T, New York, Former NWBell President Thomas Nurnburger, the Head of Public Affairs for Northwestern Bell, the IEEE History & Heritage Committee of the Institute of Electronics and Electrical Engineers Director, the Technology Director at the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of History and Technology, the Head, History Services Department of Bell Laboratories, Bell Laboratories Archival Services Branch, Director of Communications for Union Pacific Railroad Corporation and about 20 other persons whose private investment in this exercise would prove not onlyhelpful but necessary.

Additionally, a few more contacts popped up as this project was proceding. I began to meet many very interesting people along this two year path . . . Since the Internet did not exist at that time, the U. S. Mail was my medium of necessity. The wait for a response began.

How John Tyndall fit into all of this . . .

John Tyndall (1820-1893), the great Irish physicist, chemist and biologist, was renowned for his investigations of light and optics, and is regarded as the father of infrared spectroscopy. He invented both the absoption and emission spectrophotometers. Dr. Tyndall’s feather in his cap was his interest in geology. As the first scientist to scientifically describe the actions and reactions of a geyser and constructed a general theory of glacial movement, he had a broad scientic investigative reach.

Yet, not a lot of people are familiar with Dr. Tyndall. However, everyone has heard of Michael Faraday–the Director of Great Britain’s Royal Institution–the scientist of unparalleled reputation who hired Tyndall to join him as a researcher and friend for life. When Faraday retired from his post as Director, he commended and recommended Tyndall to take his head post. In his work at the Royal Institution of Great Britain and teaching elsewhere, he amassed the writing of over 30 books and over a hundred scientific papers! How’s that for quiet fame? And, he was self educated in science having largely a fine talent in mathematics and a quirky independent streak against authority. His interest in surveying landed him jobs in the railway industry.

Science was not taught at English universities during his early years, so he learned German and embarked to Marburg University–earning a Ph. D. in two (!) years!

Working with a colleague upon his return to England, Robert Bunsen, he became quite enamored of gas chemistry and attended Bunsen’s classes in organic chemistry. Now, consider: Tyndall was a scientist who discovered the effect of penicillium on bacteria decades before Alexander Fleming!

And is he relevant today? Of course! You’ve heard of “green house warming?” Tyndall studied atmospheric gasses throughout the 1860s and was one of the first researchers to recognize the earth’s natural greenhouse effect and how various gasses interplay with it (check out the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research).

To further embellish my point, John Tyndall was a rich character full of vim and vigor, with both intellectual and personal vitality to match! Having taught at various levels, with traditional and non-traditional students, his speaking style earned him a solid reputation as a recanteur. Professor Tyndall was a sought-after speaker, both in Great Britain and internationally with animated style to match his speaking style. He was, in short the “Carl Sagan” of scientific mass communication in the 19th Century.

His personal avocation of mountain climbing and intimate scientific research in glacers and geology were well known: short a minor mishap, he could have been the first person to scale the Matterhorn (he tried again and was “third” to do so), a mountain in Canada is so named for him (which he climbed), there is a glacer in Colorado, and a town in United States: Tyndall, South Dakota, which remains the one and only locality in this country named for him. His energetic nature continued right up to the moment his wife poisoned him to death . . .

. . . But we digress slightly . . . Why, then, did this town in South Dakota, county seat of Bon Homme County, come to use the moniker . . . Tyndall? In 1872, Tyndall commenced an American lecture tour. Using his scientific lecture fees, earning money on his various American railroad stocks, he accumulated enough personal wealth to establish scholarships at Harvard, Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania . . . with some spending money to pursue his mountaineering and personal travels to boot.

In short: the Milwaukee Railroad made the town–like so many other Great Plains social centers, this one had a jump start in anticipation of the developing Dakota Territory into formal statehood. Shortly before the county seat moved there in 1885, an early settler in Bon Homme county, who happened to be a scientifically trained physician, suggested lending Tyndall’s good name, and his eminent scientific association, with this growing community.

Regarding the casual connection between this open wire lead and Tyndall–our guide to the physics of light–was fortuitously and unexpectedly cunning: the very open wire which carried telephone and special circuit traffic was coming down only to be replaced by buried 135 mb asynchronous optical fiber–the very scientific nature and evolution of which, had evolved from Tyndall’s researches into the theories pertaining to optics.

End of line wrecked segment of Mitchell-Tyndall Toll Lead, 1979.

Act Two: “T” for Two

The author invites you to look into the very interesting world of John Tyndall and his research. Additionally, you are invited to stop by Tyndall, South Dakota on your way out to the Black Hills (http://tyndallsd.com/home.html). The bakery there is very excellent.

Back to our story . . . the first response forthcoming was from the Director of the South Dakota Department of Education and Cultural Affairs, offering to connect me with the Historic Preservation Administrator for the area in Vermillion at the University of South Dakota.

The State Historical Preservation Officer composed a thoughtful two page official letter in which he tentatively acceded, “I believe that the structures you describe in your letter quality for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, although they constitute an unusual nomination.”

The letters sent to the Tyndall Daily Tribune’s Editor, U. S. Senator George McGovern, went unanswered. The National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Field Representative did respond suggesting contact with the Historical Preservation Center in Vermillion, South Dakota.

Meanwhile, the Vice President and Chief Executive Officer of South Dakota for Northwestern Bell Telephone did respond to my inquiry:

Upon receipt of this letter, my emotions were conflicted. This proposal offered a “bittersweet” resolution to the preservation issue, although I felt much uncertainty within.

There were many issues which I felt had not been addressed:

First, the Tilford line was west of I-90, where access was complicated distant to the whiz-by traveler (about 1/4 mile) and was difficult to discern from the western landscape;

Secondly, there was an aerial cable on the line which I felt did not truly mirror the most potent aspects of the “pure” open wire historical recognition. This cable was relatively new and stole thunder from the exempliary open wire artifact preservation process;

Thirdly, the line wire utilized only a few pin positions of the single ten-pin 10A arm; “phantom” construction techniques were not evident;

Fourthly, the Tyndall line perpetrated a distinction from the stand point of 1931 technology: 1885-type arms, no aerial cable, varied crossarm styles: ten pin (10A), 6-pin (6A), alley arm (over 8 structures), a fully equipped terminal/junction structure with buried/underground feed, angle structures, wooden bracket construction and nearly all forms of early transposition bracket styles;

The Tyndall line accentuated four types of wire splicing techniques, insulator tying and dead-end construction practices which the Tilford line did not;

Additionally, the symbolic and coincidental technical/scientific prominence of John Tyndall’s name, lent eminence to both open wire technology and its evolutionary successor technology replacing it: optical fiber. It was the Tyndall-open wire-optics-Tyndall full circle which offered many opportunities for marketing, advertising and promotion post-preservation status;

Prudently, the preservation request was not mandating 20 miles of the line to be saved, merely a few reprentative structures in both the north and west directions. Visitors of all nature could appreciate this little stand of poles: from the casual layperson to the engineering professional;

Another consideration was Tilford line’s placement. This line was on the eastern slopes of the Black Hills of South Dakota, a little south of Sturgis. While this area beckoned tourists, without proper signing and recognition, it was lost to all but the determined and informed traveler; and,

Ultimately, south eastern South Dakota–in my mind–could use a uniquely respectable “point of interest.” South Dakota 50 was a fairly busy highway, the line easily accessible, and with local support, a feature of the landscape proudly distinguised and promoted–as a novelty of Americana.

These were the primary forces at work which I felt thrust the Tyndall-Mitchell/Tyndall-Wagner lead into the forefront of technical communications heritage preservation.

And, I furthermore felt very skeptical that Bell would actually agree to preserve the Tilford lead. It was very possible that after the Tyndall lead was knocked down, they could very well wreck-out the other lead–where I had no personal control and whose distance was unworkable from my research and accounting end. My theory was not to cast disparagement against any one Bell executive. There were abundant and powerful tidal forces at work within AT&T executive management who would do whatever it took to tear this (or these) lines down and promptly get me out of their hair so to be done with the whole matter.

My up to then, thirty year experience with utilities, had taught me never to completely trust them. While the telecommunications utilities were slightly more proficient at person-to-person management communication, they still weren’t but a few steps higher than the worst communicators in the annals of American business: the electric utilities.

Looking south, Tyndall-Mitchell Lead, during photograph survey work, 1982.

![]()

On May 12th, 1980, a kind endorsement of the Tyndall project came through my hands from Robert K. Lusch, President of the Telephone Artifacts Association in Toledo, Ohio. In his correspondence addressed to Northwestern Bell, Lusch emphasized:

“Due to the increasing number of buried cable systems, and with the advent of new technology such as fiber optics, I am cognizant that the open wire overhead toll lines will continue to be a disappearing phenomenon . . . . I urge you to do whateer you can to utilize both your personal persuasion as well as the strengths of your office to presrve that crossarm circuit.”

Several weeks later, among other supporting letters was a note from the South Dakota Historical Survey Coordinator, Carolyn Torma. I had convinced the State Preservation staff that whether or not the line could be saved, we should perform a complete photographic survey, and that this could be done through my offices. Recognizing the importance of marketing this unique event, Ms. Torma underscored our mutual viewpoint that a reply to the Bell letter should be addressed and to “discuss the subject of publicity with the company; they should certainly get some publicity for this.”

Meanwhile, my Northwestern Bell contacts were quietly working behind the scenes. One provided me with a copy of the staking sheets of the entire Tyndall-Wagner lead and portions of the Tyndall-Mitchell portion as well. These would prove invaluable as we negotiated what sections to possibly preserve and identify. The staking sheets, to those of you who may not be familiar, are composed of loose leaf pages, each with drawing of easements used by the utility, any identifying information, such as roadways, bridges, culverts, rivers, streams, railway lines or below ground obstructions such as pipelines for water, gas or petroleum. On each page, beginning from the C. O. side (source to feed) to C. O. end portion, illustrates about 10 small circles. On each circle are identifying markes such as guy wires, storm guys, number of aerial wire strands, size, class and type of pole, date of placement, ownership (as some poles may have been placed by an REA/RUS, municipal, or investor-owned utility), correlate joint use poles, bracing, types of cable, terminals, loading coils, rural wire and resident drop lines, as well as other technical features of each structure. Poles are given a number and pigeonholed on the staking sheets so that any location could be fixed quickly for repairs or replacement. The term “staking sheet” is used by both the electric and communications people. Although it is becoming rare to hear this nomenclature today with communications people.

A decade ago, when two engineers were planning a Southwestern Bell territory project, a younger engineer took notice of some existing open wire plant and asked the experienced outside plant transmission engineer if he knew what “those were?” Surprised at the fledgling’s unaffected ignorance at something he had commonly labored, designed and finally dismantled most of his early Bell career niavcomplete lack of the fledgling’s

Open wire is not the only communications technology with these “staking sheets.” Most often they are called by the new name: MPLRs, or Mechanized Pole Line Records (computerized CAD maps) of facilities. In buried systems, they are similar to open wire, except that above ground and buried facilities are noted, numbered and classified. They can be even more complex than open wire records.

Typical sample Staking Sheet of an open wire exchange line (REA).

Typical sample Staking Sheet of an open wire exchange line (REA).

Returning to our narrative, these materials greatly assisted in substantiating the line’s legal identity. Furthermore, it built a stronger case for support (within) the telephone industry by quiet contributions of Northwestern and AT&T personnel who wished to remain anonymous, yet felt my fight was an honorable and righteous one.

It was amazing to receive (in the years before the Internet) in the mail to my address, materials from unknown Bell contributors–people tacitly and unofficially acting–to support my efforts on behalf of this little Tyndall line.

Putting this information together brought me to the attention of the Telephone Pioneers Casper E. Yost Section in Omaha, who asked me to speak on this topic and give an audio-visual (yes, color slides–not PowerPoint!) presentation on this particular line, the efforts taken and the status of the project. That October 15th, 1981 performance, generated further “underground” advocates.

Act Three: Enter the Smithsonian . . .

With the Smithsonian’s long awaited and powerful political punch, the project reached a new plateau. Dr. Bernard Finn’s willingness to respond to my earlier corresondence and his organizational connections to the IEEE History Committee and their membership, was willingly accepted.

It was clear now that one little voice out here in the wilderness, along with some Congressional support, built a stronger case for the T1 and T2 preservation efforts. Perhaps we might stall the demise of the Tyndall line just . . . a little longer in order to affect some positive changes and give me more fuel to press on with the project.

Mind you, by this time, I had begun my graduate degree and was carrying 20 hours of graduate credit, along with working as a teaching assistant and . . . trying to carry the heavy burden of monitoring and maintaining this preservation effort.

On January 11th, 1982, I received the following letter from the Assistant Vice President of Northwestern Bell regarding my personal willingness to dedicate both my financial and intellectual resources to properly nominate the Tilford, South Dakota line to the National Register of Historic Places. The appropriate Northwestern Bell people were shipped a two-inch file of materials supporting the endeavor. Supporting documents were enlisted offering not only insurance for the line, financial support but a willingness to provide technical maintenance, with Northwestern Bell receiving nothing but public acknowledgement and the recipient of national advertising, should they be willing to give me the “go ahead.”

Now . . . one asks: why didn’t you write and include support documents for the Tyndall line? Was I offering the Tyndall line as a sacrifice (T1 vs. T2) to preserve the Tilford line?

No. There had been no change in my goal to preserve T1. While it would have been ideal to preserve both, this was seen as unlikely and never resulted in my mind as a viable alternative. By late December, 1981, my skepticism about Bell’s actual intentions grew to the point that I felt it was now important to create a test. Were Northwestern Bell/AT&T’s purported intentions to really save the Tilford (T2) line or was this just a ruse? Destroy Tyndall (T1) and then when I had no control, could not intervene due to distance, destroy Tilford (T2)?

So to assess their real intentions, I formulated a plan to offer everything on a silver plate. Comprehensive financing (out of my pocket) of the T2 line, complete technical documentation and photographic survey work, information application and submission of all legal documents to the National Register. And furthermore, the complete divorse of any liability of the line from Northwestern Bell/AT&T’s responsibility through State of South Dakota ownership. Ultimately, as the first successful nomination and recognition of an open wire toll lead to National Register status–considerable national marketing opportunities on their behalf would emerge.

It was to literally remove all barriers to successful completion of the project. Successfully nominate either project–at no expense to AT&T–so they could at the conclusion of the effort, sit back and bask in the reflected limelight. Who could not turn down the prospect of gratis support and full national publicity . . . at none of their expense? Several technical journals were interested in this story for the national press. There was identifiable interest by several manufacturers of communications equipment. The stage was set.

If earlier Northwestern Bell commitments to save T2 were honorable, surely they would take me up on the offer and not reneg such a magnanimous offer on my part. If they failed the test, spurned my proposal and negated preserving T2, then it was clear they weren’t going to save either line and this latest offer was a trap and quite possibly a deception.

On January 18th, I received the following letter from the President of Northwestern Bell, Jack MacAllister:

Act Four: Inimical Forces

![]()

The Tilford, or “T2 Lead,” was located in an isolated area just north of the Tilford Exit off I-90, northwest of Rapid City, South Dakota. The lead is difficult to find, unless you are seeking it. Access is difficult and only by making an exit off I-90 north of Tilford, and then doubling back on the on-ramp to I-90 East, can a traveler approach it. There is no parking, no guide signs, nor appropriate recognition of the site in any way.

The lead is distinguished from the T1 Lead, by poles’ shouldering of two “figure 8” multi-pair cables on either side below the single ten-pin arm. Because the terminal structure has no protectors, 24A Auto Transformers, NC terminals, nor carrier filters, it is not a prime asset for preservation.

Secondly, the line does not distinguish itself with phantom transpositions, although the line features push-brace structures, as required by its odd geometric travels through the hilly landscape in the foothills of the Black Hills ranges. Push braces were not used on the Tyndall line; instead all guying was done with steel cabling and earth anchors.

My major issues with preserving this line were many: the difficulty in accessing the line; no significant signage or historical considerations to point out the significance of the line; no easy access to allow a “walk up and gaze” opportunity for travelers; and it was not nominated to the National Register–a grand oversight of its promoters. There was no historical significance to the moniker “Tilford,” nor a major lead to connect large towns, as was T1.

Terminal/Junction pole removed from its original corner site and relocated prior to shipment, 1982.

Only a short distance away from where the terminal pole was stored, lay the fallen troopers of Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Here, overlooking the Missouri River, dysentery struck, killing men at their encampment in 1874.

Six soldiers were buried here (all unknown). Stars denote their service in the War of the Rebellion (1861-1865). Note Lewis & Clark Lake in the distance.

Act Five: Finale & Precipitous Outcome

T2 Emerges as the Winner

Section of the Tilford, SD aerial wire line with two figure-eight cables attached, just west of I-90.

North of the Tilford, SD exit off I-90, you will find the spared open wire lead with accompanying cabling attached. Photo taken in early November 2011.

Here is a close-up of the only transposition installation type found on this line. This pole is the fourth from the last at the north end of the lead. Drop brackets are used to transposition the pairs at this point. There were no tandem, point-type, phantom or other form of transposition on this line.

This line utilized all ten pin positions, including the pole pairs, and a recently placed new pole, was noted just at the northern end of the line. Apparently, Qwest (now Century Link) personnel have been instructed to preserve this line.

The outcome was a surprising one for this technical historian, as the successful outcome to preserve at minimum, one out of two leads came at considerable cost of time, money, effort and simple personal perseverance.

Yet, if you have a significant artifact, as this one, it does no one much benefit if it is not marked properly so that proper attention could be drawn to it as a novel feature of the region formerly served by Northwestern Bell.

My greater fear in the future is this scenario: since the line has not been nominated to the Register, and thus, lacks significant historical acknowledgement by the owning operating telco company, local, county historical or state administation, may hence be dismissed by the powers that be. They may regard this “eyesore” merely “occupying” the landscape, seemingly serving no practical purpose. I see it potentially threatened once again. Without proper recognition, the line may simply be felled by some ambitious–but historically ignorant–young whipper-snapper of a district manager or mid-level executive, making snap decisions at a distant wire center, loathe to dismantle any “insigificant asset” he/she might not appreciate for its full significance.

This is an episode which I’ve seen occurring elsewhere and my fears are not . . . unfounded. In my opinion, having talked to various former Northwestern Bell and Mountain Bell retirees, Qwest in its hayday was anxious to unload any historical baggage at all costs, was relatively–to completely unsupportive–of the Telephone Pioneers’ organizations’ members and goals, and had only recently found its “spirit of service” motto soon after customers left the company in boatloads–having never expressed a need, nor a desire to accomplish what Northwestern Bell successfully had done for over 75 years under one name or another.

It is my hope that Century Link will be much more historically charitable when it comes to both preservation as well as building and improving customer service. Maintaining their past historical connections when doing business in the old Northwestern Bell territories will benefit them greatly as they strive to re-connect with former customers lost in the recent corporate transitions.

Curtain Call & A New Beginning For Tyndall’s Remaining Artifacts

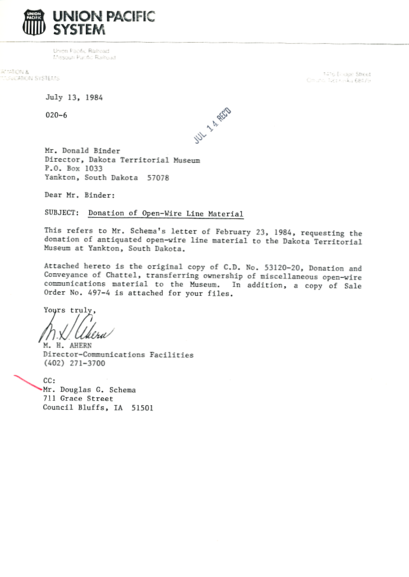

Shortly before structure was disassembled and preserved.

While saddened at the outcome of the T1 preservation effort, there was the slim possibility that Bell would save T2 (if it really existed) in western South Dakota. One couldn’t be sure . . . yes, there was a commitment in writing to Dr. Finn from the Vice President of South Dakota operations. There surely wouldn’t be any . . . intentional distortion of the truth with him . . . surely?

Northwestern Bell was apparently eager to satisfy my whims, having stirred up U. S. Congressional, institutional and organizational support, and wanted me off their backs in the worst way. The Tyndall line had received a reprieve from its death for now more than two years . . . this modest appeal effort was mildly satisfying . . . but what now?

The Bell people contacted me by phone and asked me what I wanted from the Tyndall line to mollify my penchant for this corporate disruptive behavior. My desires were simple: pull out the terminal/junction pole, cut the conductors several inches beyond the wire vices, leave everything intact on the structure, transport it to a location where my first cousin’s farm was located (half way between Tabor and Tyndall, and a little south towards the Missouri River), and I would retrieve it at a later time. Additionally, my research of some neighboring regional museums gave me the pleasure of being a dispenser of donations to their collections. While the Stuhr Museum in Grand Island did not find this equipment of interest, the Aberdeen and Yankton museums said they would definitely find a place for these saved alley-arm type structures (which paralleled the Tyndall Cemetery) and some other tangent structures.

Apparently, Northwestern Bell contacted a crane company from Sioux Falls to come to Tyndall and pull the structure out of the ground, lay it on a flatbed and transport it to my selected drop site. That must have been some project. My instructions were followed and the following summer, the structure was awaiting me. It was quite a sight! Along with it, were several alley arm structures from the Tyndall Cemetery location, which were to be donated to the Yankton Territorial Museum. The T1 preservation project had effectively ended.

Once the structure was on the ground, the disassembly part began. Since bridle wire is “black” and has the “ridge” for “ring,” it wasn’t too difficult to begin the complicated, but orderly process of cutting and tagging each pair from the two NC-25 terminals to the 24A Autotransformers and filter units on the upper arms. There was a “C” rural wire with splice, one top arm 101B terminal for a pair and drop, three drops, a buried cable at the tail of the structure and lots of pole steps–not to mention the ten BDE arms.

Once the structure was down to nearly bare pole, a means had to be obtained to lift, transport and unload the 40 foot structure. A typical 40′ class 3 pole weighs approximately 1,000 lbs. With all the pole steps, the bridling runs, two NC-25 terminals, the buried encapsulated splce to aerial lead cabling, and guy wires (four in all), this was quite a load! The crossarms disassembled neatly. They were transported separately and stored with their electronics in a secure interior location along with the pole itself.

Because I did not trust Bell to preserve the Tilford (T2) line, preserving this possibly “last” terminal structure in the five state Northwestern Bell operations territory was very important to the project and to the effort to preserve open wire technology. There was no way for me to observe the preservation of the T2 line and since Northwestern Bell had not taken my offer up to help them with the National Trust documentation, in my view it, too, was a “gonner.” And my lengthy, expensive and tedious efforts were to little or no avail.

Locally, the storage of the structures would not be a problem, as my first cousin’s husband, Jack Kreber, lived only about eight miles away. His courtesy and willingness to store the structures was much appreciated. The immediate problem of locating a suitable in-transit storage location was resolved. (See: RootsWeb:SDBONHOM-L John “Jack” Kreber 1933-2004.)

Meanwhile, all of this activity had to be monitored from afar–as I was in graduate school and things were winding down on my program in 1982 back in Columbia, Missouri–nearly 600 miles away.

Mind you, the next part of this narrative was information communicated to me by others at the Yankton Northwestern Bell Wire Center, so there are no pictures to share and information is derived from “second hand” sources. However, to the best of my recollection, this was how it went: apparently, Northwestern Bell commenced the final linewrecking of the aerial Tyndall open wire plant in the late summer of 1982. At the point where the line was nearly wrecked out, the last remaining structure remaining was the terminal/junction pole.

From Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Northwestern Bell sent a large scale crane on a truck to the Tyndall location to “pull” the terminal pole out of the ground, once the buried cable had been removed, spliced and re-terminated. The pole was gently placed on a flatbed truck and hauled to the mid-Tabor/Tyndall farm location, which prior driving directions had been provided to Bell, carried with several other structures which were chosen to survive.

Now, even in 1982 dollars . . . that must have cost Northwestern Bell plenty of money, time and labor. As regards my view, this outcome: the demolition of the Tyndall lines and the saving of a few structures for my historical technical project and that of a local museum, was something accepted in “good grace.” It was not the outcome desired or anticipated. However, the Tyndall Terminal Structure would have a life far beyond its linewrecked companions and would form the nucleus of a telecom collection at The Electric Orphanage.

The Dakota Territorial Museum at Yankton, South Dakota was chosen to receive the alley arm structure and some other donations by this author. Having talked with their director, Donald Binder, we arrived at a project which would plant several poles parallel to their existing railway depot, signalling and tracks, complete with two ten pin arms, tramp brackets and other materials. I would be willing to help out to make this a reality. Today, these structures stand on the eastern side of old S. D. 50 highway, as you pass by the Yankton Park and Mount Marty School of Medicine & Hospital.

Once information was confirmed that the structure had been secured, it took a little time to locate a properly capable construction contractor to move it. In Southwest Iowa, a well considered contractor was Paulson Construction. Several business people recommended his company as he was reasonable, conscientious and had a great record of moving (undamaged) materials to and from various sites.

I called on him at his office and explained the situation. His good natured outlook signalled to me that while this was rather . . . an unusual . . . project, he was all gung ho about assigning a driver and a long flatbed truck to move the structure. We set a time and manner of transport.

My first cousin’s late husband, a successful farmer near Tyndall, had been kind enough to house the several poles preserved from T1 line, including the terminal structure. It was adjacent to his large barn where farm implements, a combine and tractor were stored. Even though the structure was out in the open, it was secure from theft. The weather there was not very humid–being in the western plains area–and rainfall was much less than Iowa.

Once the structure had been denuded of arms, hardware and other possibly entangling apparatus, it was ready to move. I had arrived one weekend before to do this and moved those articles to Iowa. Now, it was the main structure: the pole’s turn to come down south.

Moving the pole with a front-end loader.

Anyone who knows a farmer or rancher is aware of the multiplicity of heavy equipment present on a farm. Because a farm is such a multi-purpose business, with many year-long projects such as planting, tilling, combining, fertilizing and harvesting, it wasn’t difficult to locate a front end loader to retrieve the pole, pick it up and transport it to the waiting truck. It took all of 20 minutes to perform these duties without destroying the pole in the process.

A pole such as this Class 3 40-footer, with all the steel pole steps, and attached hardware, weighed over 1,000 lbs. It is . . . essentially an adorned . . . tree trunk!

Jack was able to easily move the pole–since he worked with and represented Valley Irrigation Company’s products–and was used to long sections of pipe and rods, without any problem. One problem resolved.

We then tied down the pole on its convex side, so the face of the pole was facing up. Chains were used to secure the structure. Rolling was not much of a problem, because the pole steps had not been removed. It was a pretty stable load.

Loading the pole onto the truckbed.

No . . . its not Amarillo in my rear view mirror. The pole resting comfortably as we zoom down I-29 near Salix, Iowa.

No matter what anyone might say about this project, it couldn’t be said that my aims weren’t noble. If the Tilford (T2) line was truly going to be saved, and I had long given up on that prospect, there was no way Bell was going to communicate the progress of that effort to this author.

Essentially, the outcome of my efforts appeared to have soured, except for what now could be captured in a nutshell: in order to get you off our Northwestern Bell backs, we’ll give you a consolation prize. That prize was this structure.

Now . . . don’t get me wrong, the Tyndall Terminal Structure was one of the highest and mightiest gifts possibly expected. It was greatly appreciated. And, I knew how this artifact would reign supreme some future day at either my own historical complex or either be planted in the Greatroom of my log house! Never-the-less, this pole and the others donated through my efforts to the Yankton Museum, had given great satisfaction and capped my three year efforts.

Saying goodbye to Jack and some of my second cousins, who still lived at home in 1987, we started the trip to Iowa. Driving from near Tyndall to Council Bluffs was a 170 mile drive. Most of it was four lane (S. D. 50 from Yankton to I-29 had been rebuilt this way in the late 1970s) and travel was easy.

And, the weather was marvelous! Not too hot and not too humid. No storms in the forecast. The sky was nearly cloudless and since the truck didn’t have air conditioning, that was a mighty comfort to both of us on this early June day.

We used a Mack Truck which certainly did the job well–but my! Was it noisy! It was amazing how well the vehicle sped along the route and the driver was great to talk to, as he had done a lot of interesting work, but nothing as unique as this present job! We shared stories and the purpose of this little outing. He especially enjoyed the travel, as most of his driving had been in the Omaha/Council Bluffs, eastern Nebraska/southwestern Iowa area. Moving building materials and removing construction debris was mainly his experience–but a historical telephone pole . . . well . . . that was a little different and got him out of town for a day!

Removing the truck’s burden.

Initially, the structure was temporarily located at my former residence, where my parent still lived. The pole has since been moved to an indoor site outside of town. However, for my immediate needs–and until my work with the Yankton Territorial Museum had been completed–this would have to do.

We had several people from Paulson Construction Company meet us at Council Bluffs and they brought a material handling device to lift the half ton pole from the flatbed truck onto the driveway–not blocking–but just parallel with the northern edge. The structure was “home” temporarily and I could rest assured it would now have a “second life” as a museum relic.

I had approached Don Binder, the head of the small, but improving Dakota Territorial Museum, with an offer to donate some structures. We made arrangements to retrieve the remaining T1 structures at Jack’s farm and load them for a trip to Yankton, some 45 miles away to the east.

Since all these plans and my work with the Museum was based on my personal income alone–all my work and time was also donated to this enterprise–it was a financial struggle to help them.

The idea was to place three poles near the existing short expanse of railway track. The easement was crowded. There was a paved driveway, a strip of green grass, some railway track and several signals. One was a grade crossing signal from the old Milwaukee Road when it crossed through Tyndall, as well as a semaphore signal. There was also a searchlight type signal, too. So, as one could recognize, space was at a premium.

I suggested to Don Binder and his people we plant three poles with two arms on each typical of American Railway Association Communications Section style. On one pole had been mounted a call box, to which we would string bridle wire to attach to the lower arm and possibly run a working line betwen poles and the depot/train station immediately to the northeast. The two dead-end poles would require guying. Don mentioned that possibly Northwestern Bell could do this.

We arranged for the local utility, Northwestern Public Service Company (a utility with which I had many happy contacts), to set some older poles from their pole yard. They were happy to do this. We also had to place some guys at two structures on either end of the construction project.

Scrounging materials for use at the Yankton Territorial Museum took me to Hamburg, Iowa. Note the Type “N” arm at upper right and the double dead-end DE arms attached to the pole. These were transported and donated to the museum in aid of their exhibit.

Meanwhile, the autumn before moving the terminal pole, and anticipating the work with the Yankton Museum, my search was on for some other open wire artifacts to use for the Territorial Museum project. A former Northwestern Bell employee recommended that I go down to Hamburg, Iowa–a scant one mile from the Missouri-Iowa border, to locate some arms, deadend hardware and the like. The old Kansas City-Council Bluffs, AT&T lead had been demolished in the early 1970s and one of the contractors had kept quite a little assortment of poles and arms.

That little trip took a Saturday from my schedule and I whizzed down to make contact. Finding the refuse site from some directions the employee had given me, I approached the owner of the property, a nearby Hamburg contractor. Laughingly, he said, “Take all you want! You’re welcome to it!”

Soon, his 16 year old son was joining me as we scampered over the oversized class 1 and two poles, some with identification yet attached from their former life as a major AT&T Long Lines lead. Soon, I found a couple of good arms. Another double dead-end stuck out from the pile. There was here and there some great Type N 10-pin arms. Occasionally, some C-type deadends and bridle wire with terminals. It was all helpful. Since the teenager had been so much good help in helping me lift and haul stuff back to my vehicle, I dug out a $20.00 and handed it to him. “Wow! Thanks! That’s $20 I can really use. You’re great!”

I secured the load and looked around one last time. The day was overcast and it was in the fall when heat and humidity were not a problem. Then, the load and I set off on I-29 north to Council Bluffs to my storage site.

Early morning start at the museum.

Bucket trucks are rather fun to use, and certainly greatly aided the construction side of this project.

We had older poles installed, and my use of a bucket truck was more manageable than my pole climbing skills.

A photo from the bucket of the completed pole structure.

The open wire style we planned was based on a general American Railway Association/Communications Section criteria.

Further progress. Note the 10A and 10B arms are placed on the first structure.

We even had some Northwestern Bell local assistance. The gentleman in the bucket remembered many times having gone up and down the Tyndall Terminal Structure to replace fuses. Said, “It was a pain!”

What Could Have Been… For Northwestern Bell…

It had been the primary purpose of this endeavor to enlist Northwestern Bell’s support to preserve a technology. By doing so, their reward would result in liberating positive public exposure within the regional service area and possibly national recognition for their historical sensitivity. I was willing to assist them fullheartedly with that process, which included full nomination document processing, photographic surveying and other necessary work to build them some good marketing.

Northwestern Bell’s executive attitude precluded this.

Instead, what greeted readers of Telephony magazine in 1987, was a two page color advertisement by Rockwell International, subtitled: One In A Series On The Remarkable History Of Telecommunications. Accompanying a “Second Coming” typeface in bold, the full page color photo showed “Mule-skinner Lineman, Marvin Hanchett of Mountain Bell,” perched on a mule. The mule’s four hooves rested on an outcropping of rocks. Hanchett stood proudly. Grasping the reins of his mule in one hand and the other on the lower pipe end of a “plumber’s nightmare,” to which four insulators were afixed, with open wire lines attached, the advertisement declared:

NO MATTER HOW HIGH THE TECHNOLOGY, IT’S A SERVICE BUSINESS.

Quoting from the national advertisement:

“Marvin Hanchett, known to his intimates as the Mule-Skinner Lineman, rides the range for Mountain Bell. The object of his particular devotion is the Trans-Canyon Telephone Line, which drops down from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon and carries the human voice across territory where even the topographic maps give you vertigo.

“Primarily for use by the National Parks Service, the line is quite literally a life-saver, regularly used to call for assistance and for evacuation of disabled hikers.

“Long lines indeed. Recently awarded a listing in the National Register of Historic Places, the open-wire copper line spans the 2,400-foot vertical drop from the South Rim to rest houses, ranger stations and the Phantom Ranch far below. It is descretely hidden in the yucca plants and barrel cactus that line the 18-mile Bright Angel and North Kaibab Trails. Marv regularly patrols the line on Jim, a five year-old mule, clearing away rock slides, replacing poles and re-sagging the wire. To get the proper reach, Marv sometimes must stand on the saddle, while Jim stands fast.”

Mmmm . . . I wonder where they got the idea . . . ?

Below are some photographs made by the National Park Service of the Grand Canyon Line.